By Charlie Wilkinson

In the aftermath of World War One, Kemal Atatürk led a successful campaign during 1920-1922 which broke away from the Ottoman approach, an empire which at its height encompassed central Europe, northern Africa, and western Asia. Seeing as the Kemalist Revolution marked the end of one of the longest lasting Empires in history (1301-1922), Atatürk’s liberalisation of Turkey marked great change.

Contrary to the Ottoman approach that had preceded, Atatürk removed the remnants of Sharia law in the Turkish court system; announced absolute gender equality between men and women and separated religion from State affairs. These reforms were encroached in Atatürk’s ‘Six Arrows’, the principles of what was, a modern Turkey.

Flash forward to 2018. President Erdoğan had secured Turkish leadership once more until 2023, as had occurred in every election following 2002. The result of this grip on power? A stark contrast to the Turkey envisaged by the revered Atatürk.

What can only be described as Erdoğan’s newfound Turkey has significantly pinned back the reforms adorned in the Kemalist legacy. The ruling Justice and Development Party’s (AKP) policy line centres on desecularization of Turkey. Where Atatürk moved Islam to the private domain, Erdoğan used religion as a focal point and key instigator in society.

Turkey’s Higher Education Council announced in 2014 that mandatory courses on Islam should be taught to all students from the age of six in public schools. Publicly funded Imam Hatip Schools that follow a religious curriculum have doubled in number from 493 in 2010 to 1017 in 2015. The few secular and prestigious high schools admit only a small populous, the remaining Turkish students are automatically enrolled in such schools.

Atatürk preached gender equality, presiding over women gaining the right to vote in 1930. Erdoğan however, cannot be said to hold such beliefs. In 2014 Turkey’s President even erred that ‘you cannot make women and men equal; this is against nature’, a damning statement that is in stark contrast to Atatürk’s Turkey that saw women frequent positions of authority in court and the academic field.

Such protestations have only increased in recent years following a failed 2016 coup d’etat, an uprising for the protection of democracy against President Erdoğan. It was condemned by the State, opposition parties and the accused conspirator (a cleric who was already in a self-imposed exile in the United States, Fethullah Gülen). The actual catalysts and figurehead are still yet to be discerned.

The ramifications of the coup gave greater power to the Office of the President, a referendum was held during a time of State emergency, and powers were granted by a slim majority. Under the new constitution, President Erdoğan is now the head of the executive and also the head of State, yet retains ties to his political party. The role of Prime Minister was removed and Parliament lost its right to scrutinise ministers or instigate enquiries. Though impeachment proceedings can still be brought with a two-thirds majority, Erdoğan’s newfound powers are indeed worrisome without the presence of an independent judiciary as a last outpost to keep the government in check.

With over 140,000 people being arrested, dismissed or suspended by the hand of the State following the failed coup, including personnel ranging from journalists, academics, judges to other public servants, the fear of being labelled a terrorist sympathizer by voting against the government with the pretence of jail-time ‘casts a shadow over the outcome’ of the referendum as explained by Dr. Kasim Han. Holding a vote under these State-emergency conditions to make such a huge constitutional change threatens the very democracy the Kemalist revolution brought to Turkey in the early twentieth century.

The sentiment was repeated by U.N. human rights chief Zeid Ra’ad al-Hussein who noted that ‘it is difficult to imagine how credible elections can be held in an environment where dissenting views and challenges to the ruling party are penalized so severely. Judicial independence has already plummeted to 151 out of 180 nations, with press freedom falling to 157 which follows from 90% of Turkey’s newspapers being pro-government (Reporters Without Borders).

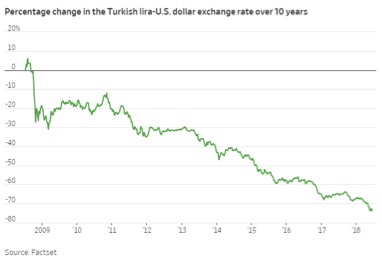

With the Turkish lira in drastic decline and democracy falling off the cliff edge, how has Erdoğan nevertheless retained a strong majority, even in the face of a fairly unified opposition which has seldom happened before?

One of the reasons why Erdoğan is still heavily supported is that after the Kemalist Revolution in the 1920s, a stigmatized conservative class was left in favour of the population at large. The present electorate have not looked at the imprisoned public servants or fall in foreign investment, but a global conspiracy against Erdoğan, and thus Turkey, and this has been cemented in the minds of many voters by the 2016 coup. A poll by Xsights in 2018 finds this Western conspiracy plausible, far more than even Erdoğan’s political base.

Erdoğan’s sentiment that whoever wins at the ballot box has the absolute will of the people was affirmed to the President and his supporters in the change in constitution following the 2017 referendum. Though not a liberal democracy as seen in the West where freedom of speech, press, an enforced rule of law, an independent judiciary, property rights, and academic freedom are all paramount, Erdoğan’s elected mandate is democratic nonetheless in Erdoğan’s eyes.

Others welcome the reversal of Kemalist secularization, wanting Islam to be entrenched in the State, through education as well as politics, regardless of the actions of Erdoğan’s government in relation to the economy or foreign policy, particularly with re-engaging the Middle East and furthering Turkey’s status as a regional Sunni power.

Whether Erdoğan’s changes in modern Turkey can be detailed as a reversal of Kemalist reforms and an attempt to remove Atatürk’s revered status still in the Turkish public’s eye, or indeed a revolution, makes little difference. What is certain is that as Erdoğan deepens his political power, Turkey will only move further from the secularised State envisaged by Atatürk.

What of the future? Though Erdoğan’s position as President is confirmed at present until 2023, local elections in early April 2019 have shown that though in power for over fifteen years, the Turkish President is not untouchable. The AKP lost several leading cities including the capital Ankara, and Erdoğan’s hometown, financial capital and where he presided as mayor at the start of his political career, Istanbul. Might Erdoğan and the AKP’s leadership be drawing to an end, or will the President only tighten his control in time for the 2023 elections with his role’s newfound constitutional powers?

(Atatürk left, Turkish flag center, President Erdoğan right)