This week features the second article in the series on challenges in securing human rights for persons with mental and psycho-social disabilities. The right to legal capacity is logically the next topic to visit because it forms the very basis for any person to make their own valid decisions about their mental health and treatment.

While the gravity of certain mental disabilities can sometimes inhibit the ability to make an informed decision without assistance, the Mental Disability Advocacy Centre—a leading NGO in this field—notes that the practice of some states in response to this challenge are problematic. This article aims to consider what legal capacity is; what the consequences are of living without it; and what kind of system can best ensure choices in the interest of those with disabilities, without eroding the rights conferred on them as persons under the law.

What is Legal Capacity?

The law endows its subjects with legal capacity in order for them to function within it as an autonomous individual. Essentially, it confers a power to make decisions about our own lives which are conversely recognised and respected by the law.

It is hard to imagine life without the right to legal capacity. The range of personal activity it facilitates is vast: one cannot enter contracts without it, employ the services of a lawyer, own property, or even vote. That legal capacity forms the basis of our independence is no stretch of the imagination, particularly if we consider going about our daily lives without it.

Even more alarming is the realisation that where one has no legal capacity, their access to justice in the event of mistreatment is compromised. Removal of legal capacity therefore not only strips the individual of the ability to make decisions for themselves about fundamental aspects of their life, but it also prevents them from directly enforcing their own rights.

Guardianship—friend or foe?

All of us are born as persons under the law. Crystallising with adulthood, this is not a status we apply for; it is a birth-right. The law is therefore required in instances where a person’s legal capacity is to be removed. The process usually takes place as follows: a medical expert will make a recommendation to alter a person’s legal capacity, whereupon a court will order the stripping of legal capacity if the judge agrees that the individual cannot make decisions for him or herself. In lieu of legal capacity, a guardian will be appointed to the individual and acquire absolute power of substituted decision-making.

Alternatively, when children with mental or psycho-social disabilities come of age, they are often automatically assessed as incapable of making informed decisions and immediately appointed a guardian in many national healthcare systems. Under an informal guardianship system, the responsibility is assumed by a relative.

While the word guardian conjures notions of duties of protection and overarching concern for the best interest of the individual, it is important to note that often a formal guardian is appointed who has no prior personal relationship with the individual. The law might envisage the guardianship system as a just substitute of legal capacity, but practice shows it paints a less rosy picture.

The MDAC in their research has found that many states which administer a guardianship system thereby create the right conditions for widespread abuse of that power without assessment of individual cases. For example, many adults are arbitrarily placed in mental health institutions indefinitely by their guardians. By the same stroke, individuals are robbed of the ability to vindicate their rights in light of abuses, for their ability to file police reports or legal cases in their own right are compromised. It’s no wonder that Article 12 of the Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities asserts the right to legal capacity for all on an equal basis.

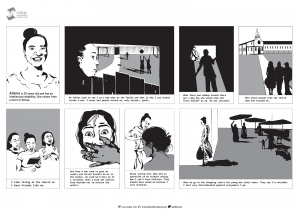

Another common practice of guardians is the forced sterilisation of women against their will. This is a problem the MDAC picked up on in researching for their report The Right to Legal Capacity in Kenya, produced in collaboration with local human rights bodies. The following true story illustrates this abuse of formal and informal guardianship:

Such flagrant human rights violation should not be occurring and should certainly not be sanctioned by a guardianship system imposed by the law. How do we ensure a system is in place which reconciles the inalienable rights of persons with mental disabilities with the reality that they may need help in making life decisions?

The Way Forward: Supported Decision-Making

One matter is clear: absolute removal of legal personality is unacceptable. It risks violation of human rights and the denial of access to justice. The MDAC therefore recommends its abolishment in legislative practices in the strongest terms.

To replace guardianship, states need systems which strike the right balance between assistance in making personal choices and respecting the autonomy of the individual. As this equilibrium depends on a person’s cognitive capacity, which vary significantly between individuals, a flexible approach needs to be adopted. The MDAC advocates a system of supported decision-making, which leaves legal capacity intact, but provides the framework for assistance based on a relationship of trust with the supporter. The system envisages the supporter’s duty to ensure the individual understands the background and options when faced with a decision, but ultimately it is the individual who makes the decision.

Regardless of the system adopted, it should not reflect the archaic view that people with mental disabilities in exercising their right to autonomy pose a danger to society. When making tough decisions about policy, some states need a little help.

Cover image: Flickr/Jacob Windham under Creative Commons licence.